A Blog of Personal Thoughts

Positive Interactions for Peace

February 2026

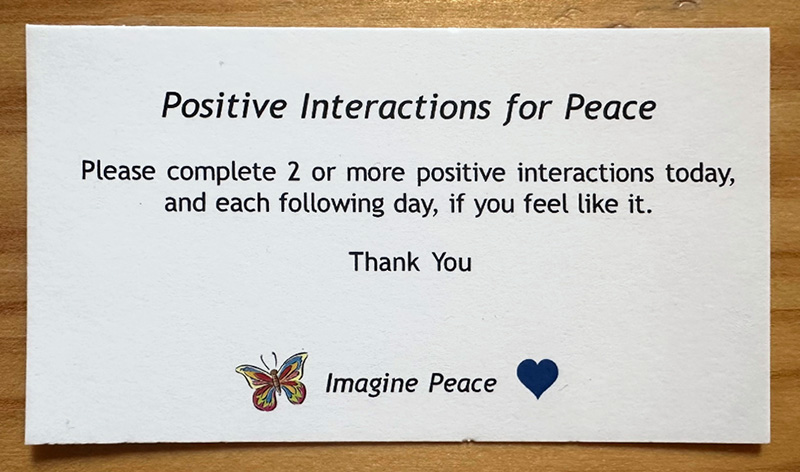

I sit in my study looking at a strong east wind blowing the tops of the spruce trees. The smoke from our woodfire blows from the east, south, or north, depending on the whim of the wind in our small clearing in the woods. Looking out the window in front of my desk is a pleasant distraction as I think about the state of my country—a mess. A comforting thought comes when I look at the card Jack sent me. It says Positive Interactions for Peace.

Wanting to make people respond to one another more positively, Jack Auman, a longtime colleague and friend, changed his behavior: he initiated positive interactions with strangers. These included anything from a wave and a smile to asking if someone wanted a hug. As he progressed with these interactions, he developed this card to hand out to strangers. He recently sent some to Governor Tim Walz and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey. I sent some to Louise Erdrich, the owner of Birchbark Books in Minneapolis and to the Friends (Quaker) Meetings in Minneapolis, St. Paul, and the 15th Street Meeting in New York City; I grew up in the 15th Street Meeting. I also sent some to The Penington, a New York City Quaker residential hotel where I lived for a year as a child.

When I go to town, Juneau, this weekend I’ll also hand them out randomly.

|

The business size card Jack developed. |

This past fall, Mandy Mason from Australia, interviewed Jack and me about Positive Interactions for Peace. The hour-long interview is available at https://theabaandotpodcast.podbean.com.

I’d heard of the butterfly effect, but had discounted it. How can a butterfly cause a change in the universe? It comes out of chaos theory. It’s a metaphor meaning a small phenomenon somewhere on our planet can change something far away. Edward Lorenz, an MIT meteorologist, gave a talk in a 1972, during which he asked, "Does the flap of a butterfly's wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?" I don’t know its literal accuracy, but metaphorically it’s perfect.

One example is the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand. The driver of his car made a wrong turn, putting the archduke in the path of the assassin’s bullet. It was 28 June 1914. World War I began a month later, July 28, 1014, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. I learned that when I was a little girl, perhaps four or five. Why so young? Because 28 July 1914 was my mother’s 15th birthday. She never let me forget that World War I started on her birthday. She also reminded me of when The Titanic sank, she was 12; or when she first heard Yehudi Menuhin play, she was 13; or when her great-grandmother, Hannah Steele Witmer, died, my mother was 14. Grandmother Hannah’s grandfather was one of George Washington’s aide de camp during the American Revolution. All this was personal to her, which made it personal and real to me. The death of Archduke Ferdinand and the beginning of World War became a butterfly wing to me.

Or there was the time when Richard, the son of a friend of mine, had a dream about a car accident, which occurred a few days later. Had Richard not had that dream, he would have been involved in the fatal accident.

What causes these major or small occurrences to happen? I don’t know, but I’m willing to go with chaos theory and the butterfly effect. Thus, the butterfly on the PIP card Jack has made and gives out. Perhaps one of these cards will land in the hand of someone who will make a difference in someone’s life.

Someone in Ukraine recently said:

Alaska clothes would have been really handy (though I wear my Columbia coat and uggi, have a few blankets when I sleep, heavy weight socks and hat) and this rubber thing—kind of a heater you fill with boiling water, and it keeps warm for hours. All this is not normal, but we keep moving on, living on, adjusting, inventing the ways to warm up and carry on.

If this person can live in a war zone and say this, I hope my readers can have two positive interactions a day, every day.

At the least having two positive interactions each day can make a significant difference in someone’s own life. It will make a difference when you give two positive statements in one day. It is kind. It is generous. Also remember, if you don’t have anything nice to say about or to someone, don’t say anything at all. Better yet, say something positive.

Please complete two or more positive interactions today.

|