A Blog of Personal Thoughts

Timeless Silence

November 2025

Silence…

Silence of the Fifteenth Street Meetinghouse…

Silence of the souls that fill it…

Silence of a solitary walk in nature far from civilization…

Silence is the complete absence of sound.

Far away in Alaska’s winter woods bits of sky poke through branches of tall spruce and hemlock trees, trees too tall to see their tops from inside the house. Outside on this frosty day, snow occasionally thuds off one of the trees. Unless listening very carefully, flakes fall soundlessly. A snow blower whines several hundred yards away. Inside the cabin, the wood fire crackles.

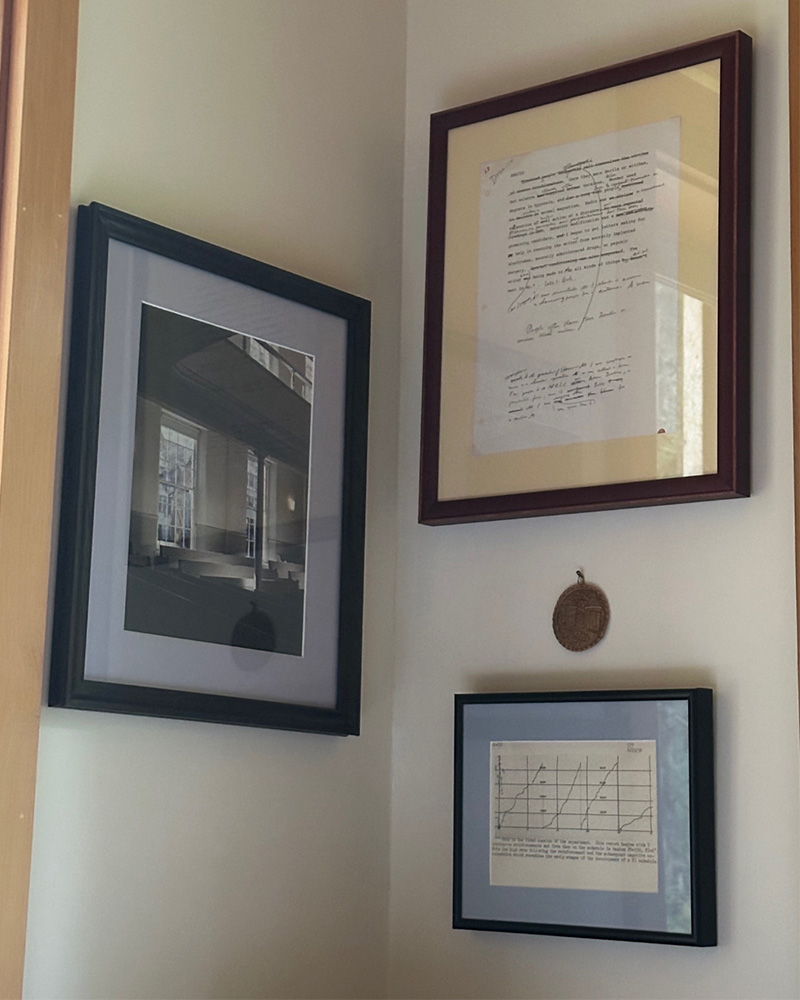

My studio sits in silence or music plays—Russian Orthodox chants, Shostakovich, Beethoven, Gorecki, Native American flute music. A photograph of the interior of Manhattan’s Fifteenth Street Meetinghouse hangs on the wall front and right of the desk. Alongside it is a page of one of B. F. Skinner’s marked up manuscript pages, an image of one of his cumulative recorder records, and a round leather image of Tolstoy’s Yasnaya Polyana, his birthplace, and home till his death. These four items hang at the corner between windows, objects for contemplation on thought and silence.

In the Meetinghouse lives silence with cushioned benches, a quiet creak of wood. An arch rises and curves upward and out above the facing benches. Its warmth embraces the silence of an empty or full meetinghouse. Perhaps the Inner Light shines, fills the gathering, and perhaps a child’s wandering thoughts. The child hears birds, blossoming trees, and traffic through the open windows in spring, perhaps the gentle soul of Miss Thomas, the Lower School head in the 1940s.

|

15th Street Meetinghouse, two images from B.F. Skinner above and below the wood sliver disk of Yasnaya Polyana. |

Skinner worked in the basement study of his Cambridge home. No one heard his talk or movement. With his solitary thoughts he wrote and edited a page that he started with “People often blame their troubles on unseen troublemakers. Once they were devils or witches, but science offered other versions.” He edited those two sentences in five places. This single page hangs at a right angle to the Fifteenth Street Meetinghouse photograph a reminder that a page is rarely complete in its first draft. His writing of decades ago offers any other writer a stimulus to do just that, fine tune writing for the reader.

Beneath that is Yasnaya Polyana. The small leather circle of an image of Tolstoy’s 4,000-acre estate represents the silence of the fields where his people, who lived on his estate, cut hay. Some days he went out to join in the hay cutting, not something noblemen usually did in those days. The lakes reflect the calmness of the sky, the release and peace after a long day’s work. He wrote Anna Karenina and War and Peace in the silence of his study. Except for this study, the house did not have silence for he had thirteen children. No matter how well behaved, they brought noise to the house. The surrounding woods and fields offered plenty of silence, though.

Below the image of Yasnaya Polyana, hangs a framed cumulative record from Skinner’s lab from August 1952. This image reminds anyone to measure human behavior as he and his student, Ogden Lindsley, did.

I have lived in the noisy environments of New York City, London, Edinburgh, and smaller cities. I thought little of it other than any of those locations had little silence and often overwhelmed me with a headache of noise. Somehow, though, the noise of New York, while there, did not penetrate the walls of the brick Meetinghouse. I remember hearing birds or cars in the spring and fall when the windows were open during Meeting or our senior study time on the gallery benches. It seemed easier to study there than in the school’s library or homeroom.

I lived at The Penington, 215 East 15th Street, New York, during my second-grade year at Friends Seminary. My parents’ room was on the second floor overlooking 15th Street. My room was on the third floor in the back overlooking the school playground and some sort of back alley if I looked towards Third Avenue. I had my own room at our Massachusetts home, but this year in New York was special. In those days, September 1948 till June 1949, I really had my own room. There was no running to my parent’s room in the middle of the night if I had a scary dream or did not feel well. I felt quite the mature seven-year-old. My mother tucked me in each night, but then I was on my own till I awoke with my alarm, dressed, and went to my parent’s room to tie my father’s tie in a double Windsor knot before we went to the dining room for breakfast.

After breakfast, I walked out the door, down the steps, to the first gate of the Meetinghouse. When unlocked I entered the yard there, walked around the Meetinghouse to the front door of the school. If that gate was locked, as it often was, I walked around to the Rutherford Place entrance. The day was noisy in the classroom. I formed some friendships that lasted forever—Sturges, Tony, Elizabeth, Rick, Corrinne, Nancy, David, Stephen, some of whom I never heard from again, but they live in my memory. Each of us put together our own book, bound with three rings and fronted by the hard cover that said Friends Seminary. I still have mine and it resides in my study in our home in a small ranching town in southeastern Oregon where the next town of any size is 100 miles away.

Surrounded by ranchland, hills, desert, and vast empty spaces, a half-mile walk finds me in the silent hills that rise 2,000 feet above the town. Or perhaps, sometimes my husband and I drive out to the old family ranch 80 miles to the east.

|

Robert walking a field in Guano Valley in March. This is where Grandfather Barry ranched. |

Such silence. I can hear the wind, birds, or silence. The now-deserted ranch house has no electricity, running water, or any other amenities. Unlivable now, it belongs to the BLM and is inhabited by swallows and perhaps field mice. My fantasy is to live there for months. I could write, longhand, with only the sound of my pen. I could hike through the sagebrush with only the sound of my footsteps on hardened sand and soil. Living there will never happen, but some nights my husband have spent in the desert sleeping in the open back of the truck listening to coyotes and watching the star-filled sky.

Where we live in Alaska is off the road system, approachable only by small plane or boat. It is silent here. Again, we might hear wolves or coyotes at night. Some nights I drive up to Glacier Bay National Park entrance by the open muskeg where there is a clear view of the sky. I watch meteor showers or northern lights.

|

A silent field in Gustavus. |

What gave me the appreciation of silence was the calmness of the Meetinghouse on First Day mornings. I felt relaxed sitting between my parents on one of the benches. Even as a seven-year-old, I liked it. Even with the city noise outside, I appreciated it. Even though my father always called it the noisiest meeting he even attended, that is, too many people stood to talk, I liked the silence between those who spoke.

Now I live in the silence of nature.

|