A Blog of Personal Thoughts

Fleetfoot the Cave Boy

August 2021 Many animals have been killed and many others agonizingly wounded in the Bootleg Fire in southern Oregon. A rancher found both cattle and wildlife burnt to a crisp. Along a particular road she (the rancher) also found a burned fawn, a mountain lion and three head of cattle still on fire. Her statements made me think of Fleetfoot—the Cave Boy, by William Nida, published in 1929. Twenty years later, this was my second grade reader.

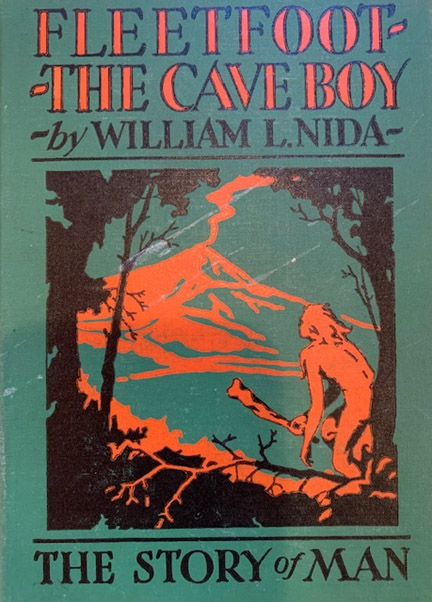

I loved that book. The cover is a black and orange image on green. A volcano is in the distance and Fleetfoot in the foreground. Its text is green, unusual I thought then and now, and its illustrations in black, brown, orange, green, and white. It was the story that charmed me. It starts with all living creatures, people and animals, fleeing from a forest fire. A saber tooth tiger comes to a river, but rather than cross it, he runs back into the fire. As Fleetfoot and his family ran, the boy becomes separated from his family.

|

The next to the last chapter is titled “Hunting the Great Mammoth”. It was then I became enamored with mammoths and mastodons. That year we lived in a small New York City residential Quaker hotel, The Pennington. My March 2020 Personal Thoughts blog, Cats in the Kitchen, described some of my life then. My mother worked at Lord & Taylor’s and my father, a chemical engineer and consultant, had his office at 500 Fifth Avenue, the corner of Fifth and 42nd Street. With nothing to do on weekends, one Saturday my mother asked what I wanted to do.

“ I want to go to the Bronx Zoo.”

“What do you want to see there?”

“I want to see the hairy mammoths.”

“Oh, Honey,” she began. We went to the Museum of Natural History.

I was horribly disappointed. I wanted to see living mammoths not skeletons in a museum. For 50 years since, I steered clear of natural history museums. One day in Whitehorse, Yukon, I went to the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Now I had found my museum of long ago ancient animals that made that era come alive.

I learned that mammoths and mastodons are not of the same species. Mastodons existed about 30,000 million years ago. They lived in Central and North America. Smaller than mammoths and with a flat back and long, shaggy hair reminding me of a yak, a short mastodon was about the height of a contemporary adult moose, perhaps 7 feet. They also ranged upwards to 14 feet. They ate leaves, twigs, and branches. That was lot of crunching.

|

Half a mammoth tooth, about 6 inches long, whose chewing end faces the camera. |

The mammoth came about 5 million years ago in Africa and roamed Europe Asia, and North America, probably crossing into North America over the Beringia land mass. Like mastodons, they were vegetarians that grazed much like present-day elephants and cattle. Although elephant backs don’t slope like mammoths backs do, the elephant of today is related to the mammoth but not the mastodon. I was very excited when I learned that there were some wooly mammoths on Wrangell Island, off the northeastern coast of Siberia, as recently as 3,700 years ago. I wish I could have been around then to see them. If they were still there, Wrangell Island would be the first on my list of places I must go within the next months or year.

I now live far from New York City, as far away as one can get in culture, geography and distance. New York City is flat because it was glaciated. Gustavus is also flat, but only one of two flat places in Southeast Alaska. Why? Because a glacial outwash plain took the soil away. Gustavus lies between the Chilkat, Takhinsha, and Fairweather mountain ranges. The town is on a peninsula that is about 40 miles away from the Ring of Fire, or the ring of mountains that goes from Tierra del Fuego up the coast of South America and North America across the Bering landmass and ocean to Kamchatka, Japan, and on down to New Zealand. Think tall mountains that border the Pacific Ocean. Think volcanoes and earthquakes. In Alaska and Kamchatka there are few people. Here we have lots of wildlife such as bears, moose, coyotes, wolves, bald eagles and about 300 other bird species, humpback and minke whales, orcas, seals, sea lions, porpoises, and the occasional deer or fox. Anyone can come or leave by air or boat, but because of ocean and glaciers there are no roads in or out.

Some days when I walk to about a mile from my house and into Glacier Bay National Park, I see a mastodon or a mammoth come through the brush. I wish this were true. Just like with the animals we have here now, I know to respect that this is their territory and I’m the newcomer here. I give them wide berth to respect them. I even give a vole and a shrew wide birth. I would do the same if I saw a mastodon or mammoth. We may have a house here, but they were here long before we came. The mastodons and mammoths were here long before the glaciers of the Ice Age 20,000 years ago and the Little Ice Age of 1,000 years ago.

Fleetfoot was very significant for another reason. That year I learned my name. It was not Gail Calkin as my mother insisted on calling me because Abigail was too old-fashioned. It was Abigail Burgess Calkin. Standing testimonial to that is my inscription in Fleetfoot—the Cave Boy. I had originally written Gail Calkin, but amended that to

I found it impossible to convert my mother to my correct name—she called me Abigail only once and that was in a last month of her life. My father found it easier, though, and he occasionally called me Abigail. That pleased me. My siblings took a while, but they too converted to Abigail. It was Fleetfoot who led me to expand my knowledge and who let me know what my name really was.

|