A Blog of Flashbacks Captain Tom

July 2022

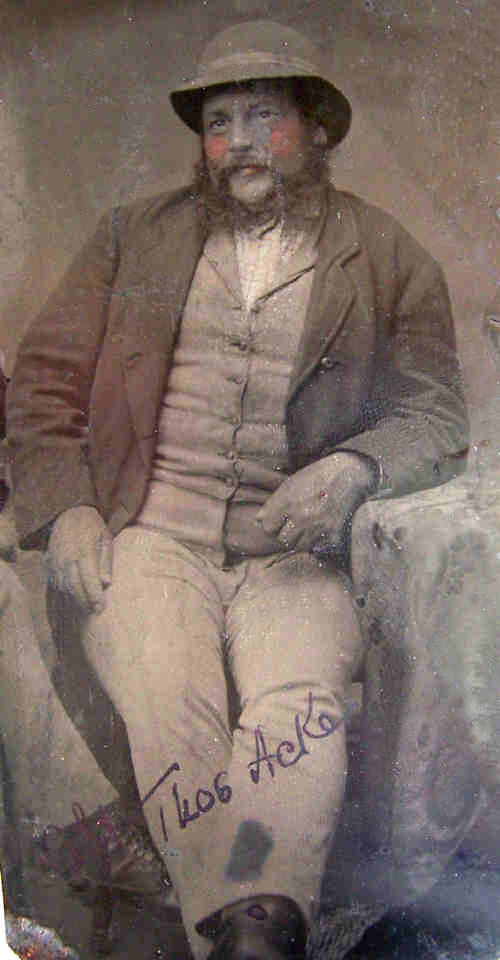

Tom had been a slender young boy who plumped out as he grew older. By the time he and his wife had three children, his vest pulled at his captain’s buttons and his trousers tightened at the seams. When serious, he had furrows that crossed his forehead and two deep vertical lines between his dense eyebrows. His thick moustache joined his muttonchops beard. Though he was not a handsome man, Captain Tom was comely enough. His eyes were the color of the sea on a calm day when the water reflected blue from the clear heavens. His large pupils were as black as angry water in a storm. His eyes lit with laughter on his happy days and he couldn’t help that his mouth carried a grin no matter if he was trying to look serious or stern. His hidden smile came on land in the presence of his family and it came each time he headed out to sea whether from his homeport of Lunenburg, or to or from Labrador, the warm islands of the Caribbean or any port between. His fingers, which were short and wide, had grown muscular and always swollen from a lifetime of working dory oars and the lines of the brigantines and schooners he captained. They were a workingman’s hands. It was his habit to wear wool for it shed water and kept him warm in Nova Scotia’s chill, salty weather. Wool clothed his body with a warmth he relished.

|

Capt. Tom Acker, my great-grandfather. |

His obituary read:

The remains of Capt. Thomas Acker, of the brigantine G. W. Pousland, reached this port on Monday last. The flag at half-mast, as the vessel came up the harbor told the sad tale of death on board. The captain of the ship yielded to the power of a mightier captain, who in his power will have to yield to a higher and superior dominion. Captain Acker died on the 28th of November, eight days after leaving Turks Island, and after a few hours sickness. Beloved by his officers and crew they would not commit his remains to the stormy deep, but resolved on bringing them home for the comfort of his family, and for internment among those he had loved in life. Thirteen days after his death a large and solemn procession was seen wending its way from the landing stage on the wharf, passing his home, to lay him with the grand words of the Church of England burial office in his quiet grave where

The storm that rocks the wintry sky,

No more disturbs his calm repose

Than summer evening’s latest sigh

That shuts the rose.

Capt. Acker was 46 years of age, leaving a widow and three children to mourn his sudden death. He was brother-in-law of Capt. Burns, of the Lunenburg packet. All honor, I say, to his first officer, Mr. George Hall, and the men under him, for their consideration done to Capt. Acker’s family and friends. It will ever be held in grateful rememberance.

Lunenburg, Dec. 12.

[The spelling and punctuation are the newspaper’s.]

This Capt. Tom, as we his great-grandchildren call him, had a sense of humor. Why do we think this? Because of his facial expression when photographed and because those of his family’s descendants also have wit and humor.

Although he vastly would have preferred to arrive home alive, I’m sure he would have enjoyed how he came home in his death. His crew had put him in the pickle barrel to preserve his body. I asked a friend of mine, a doctor, would the church have smelled of pickles, or of a pickled, well-liked captain. He thought for a moment, concluding that, after two weeks in brine, he and the church probably smelled a bit briny. I think Capt. Tom would have smiled at that. I know his look-alike grandson, my father, found that story very amusing. It was probably also appropriate because, as my cousin Ingrid said he was often known to have been a bit pickled on the rum he frequently drank.

But the humor ended there. Two years later, when my grandmother was now 14, the oldest of Capt. Tom’s three children was washed overboard, lost in the sea he loved. Grandma’s other brother had finished school and moved to Halifax. The widow, Rebecca Burns Acker, and her now-16-year-old daughter moved to Truro for Mary to attend Truro Normal School and become a teacher.

She met and married Will Calkin, son of the head of the school. As the result of scarlet fever, Will became deaf, gave up his dream of being a teacher.

Tragedy did not end there either. Will and Mary moved to the States so he could get a master’s degree in chemistry. He spent his life as a lab chemist for Gladfelter Paper Company in Pennsylvania. They had one daughter, Dorothea Belle, who may have had a spinal defect as she always sat with cushions behind her. Mary’s mother, the widow, Rebecca Burns Acker, lived with them in the States.

Rebecca, Mary, and Dorothea all came down with typhoid fever. Rebecca died as did little Dorothea a week later. Afraid he’d lose her also, her husband, my Grandpa Calkin, never told Grandma her mother and daughter had died till she herself was well out of danger. Mary and Will had two more daughters who never lived past the first day. My father came along last and grew up to look just like Mary’s father. The first time I saw a picture of Capt. Tom I burst into tears, so strong was the resemblance of the two men.

|

John B. Calkin, chemist, my father, and grandson to Capt. Tom. He was born 27 years after Capt. Tom died. |

I’ve always felt sorry for Grandma Calkin. By the time she was in her early thirties, she had lost six people who meant the world to her, three who had shaped her world and three whose world she hoped to shape. She made four octagonal star quilts and four braided rugs. I’m sure they were for her four children. My two sisters, one brother, and I all received one of each.

Inheritance

Infant daughter, born 1903,

Wrote my great-grandmother on October 31.

Of Wm. & Mary Calkin, added the mother

In later years when the book became hers.

Dorothea Isabella, born 1895, died 1901

Wrote my great-grandmother.

Infant daughter born 1897,

Of Wm. & Mary Calkin, added the mother.

My grandmother was childless.

My grandmother was childless--

two daughters had died--when

she became pregnant in the spring of 1903.

How strong her prayers, how high her hopes.

October 31, she lost one of the twins.

Three daughters gone and still pregnant.

Will this one live? How high her fears

How deep the knife--

She gave me this as her legacy.

Her son grew with her frets and fusses.

This overbearing (or is it overweight?) German woman

Knelt behind the bench one arm slung

Across the shoulder of her husband, the other around her

Son and sole link to the future.

She held her first grandchild, a girl named Mary,

Like a sack of potatoes brought from the store.

Don't let me hold this daughter of my son, love and lose her

Was writ all through her arms. Yet in another photograph

Her husband cuddled his granddaughter like a young man in love.

She bore the scars. Gave them to her son.

Left them to me in her will.

I buried them last decade.

But no one had ever told me my father was a twin

Not until I found my great-grandmother's

and grandmother's handwriting in The Shakespeare Book.

My grandmother once said to my mother, “I don’t know why you got to keep all three of your daughters and I never got to keep one of mine.” Such pain, Grandma. My mother had no idea what to say and said nothing. I was probably forty before I figured out a possible response. “I am so sorry. Please enjoy mine for they are your granddaughters.”

I wish she had lived longer so I could have known her better. I am glad she died before I was deathly ill for months with scarlet fever. I know she would have suffered with memories and I never wished that on her.

|