A Blog of Flashbacks Ogden Lindsley & Precision Teaching

December 2022

Like so many other young men in the 1940s, Ogden enlisted in the Army Air Corps in January 1942. He came from Rhode Island and from old New England stock. At three years old, someone took a photo of him beating a drum and carrying an American flag for his own July 4th parade on the family farm. Advance a few years from 1926. Here was a nineteen-year-old in his sophomore year at Brown University, who was prepared to prove his patriotism, drop out of college, and go to war for the United States. Soon he would be Pfc. Ogden Lindsley in World War II. Two decades after that, the association would be Ogden Lindsley and precision teaching. The why will become clear.

He became a flight engineer and was soon off to the European theater based out of Italy. In one of those crazy stories that takes decades to reveal all its pieces, Ogden always said he was a grandfather by the time he was 21. That meant that many of the diverse crew with whom he flew had gone down and been killed. Crews on a plane were not always the same, but they tended to know the people they flew with.

Pick a day, any day, during what we now know as the last year of the war. All countries had lost hundreds of planes and thousands of men, perhaps thousands of planes and tens of thousands of men. The planes were now old and the crews new to one another. On a July day, July 22 in particular, a crew was called to fly. Chance had flown the plane the day before and redlined it, meaning he labeled it unfit fly. Due to a shortage of planes, the Army Air Corps did not have time fix this plane, but called the next pilot on the alphabetical list, Chancellor. Flying an unbeknownst redlined plane with an unknown-to-one another crew, they left Leece, Italy to bomb the Ploesti (Romania) oil fields, probably flying through flak as they released their bombs. Bombing mission successful, they headed back to Leece, when the redline issue reared its deadly head. The oil pressure gauge did not read correctly and flight engineer, Lindsley, in charge of fuel and oil, knew nothing of that. With oil not feeding the engine correctly, the plane crashed a couple of miles short of the Adriatic Sea. Before it crashed, the pilot hollered at the crew, “Bail out!”

In the chaos of a plane going down and people bailing out, someone pushed Ogden out of the plane. He had only one parachute strap fastened. Somehow, falling, he managed to get his arm through the other strap and do whatever he needed to do before deploying the chute.

Two crew members died in the bailout and Germans soon took the others as prisoners of war. Ogden and his crewmates were POWs. On his 21st birthday, August 11, he and the others arrived at their first Stalag.

There are clear reasons why the military training is what it is. Learn how to fly through flak. Learn to maneuver through an unknown field with a new set of buddies. Know your role during the constant confusion of battle. Keep the fog of war away from yourself. Follow orders even when they are orders you received a day or a week ago. Attend to what is immediately in front, beside, and behind you. And much more. In other words, a lot of training goes into making all the rules second nature to success and survival. Some of those rules also apply to how to survive as a POW.

Og shared several details of prison camp experiences. In winter mornings he often awoke having to move his shoulders to crack the ice that had formed on them. The forced march to another Stalag a few hundred miles away to stay ahead of the squeeze the Russians to the east and the Allies to the west had put on Germany. Going out under German escort with two Frenchmen to fetch firewood for the camp, enabled the three of them to escape when a small battle broke out between the Germans and the Allies. Hearing a vehicle and fearing it was German, the three stopped. It turned out to be a British one when the fellow stuck his head out and said, “Hey, blokes. Want a smoke?” and tossed a tin of cigarettes at them.

Og, at 6’ 1” now weighed tens of pounds less than when he had enlisted. There being no US nearby, the British outfitted him in one of their uniforms before sending him to the nearest American installation.

|

Ogden in British uniform after his escape from a German POW camp, 1945.

(Courtesy of Nancy Hughes Lindsley) |

What did Og do with these lessons he’d learned from his war experiences? Like many from Company E of The Band of Brothers, he learned he needed to devote the rest of his life to helping make sure this never happens again. In Ogden’s words, he would spend half the rest of his life having fun for those who never came back to enjoy their own lives, and he would devote the other half to finding a way to prevent any future occurrence the travesties of World War II had brought. Have fun he did and his ribald laughter, guitar playing, and even ranching showed that aspect of him.

What does precision teaching have to do with this story? Ogden returned to Brown University to finish his bachelor’s degree and earn a master’s before leaving for Harvard University to end up with B. F. Skinner as his PhD advisor. Skinner told him to teach a rat, Samson, to high jump, but Og taught him to weight lift. Out of the military and true to his own form, Og did something different. He watched what the rat did, learned from him and taught Samson to weight lift instead. Skinner praised him for his creativity in changing the task. To shorten a lengthy story of almost fifteen years into two sentences: Og took the principals of animal behavior to residents of Metropolitan State Hospital in Waltham, Massachusetts and taught psychotic people to change some of their behaviors. From there, he moved to Kansas where he continued his lifetime work to help us find ways to better educate people in his efforts to prevent the future occurrence of the travesty of World War II. This now includes how to improve learning in all academic areas as well as diverse human behavior areas such as interpersonal relations, personal skills like increasing positive thoughts and feelings while reducing negative ones, the business world, nursing, improving sports skills. How did he teach thousands of people to do this? By looking at the frequency (how often something occurs in a given time) of a wide variety of behaviors, monitoring them daily, and changing them as necessary. He termed it precision teaching meaning how to teach more precisely and efficiently to enable the learner to learn more quickly and retain information better.

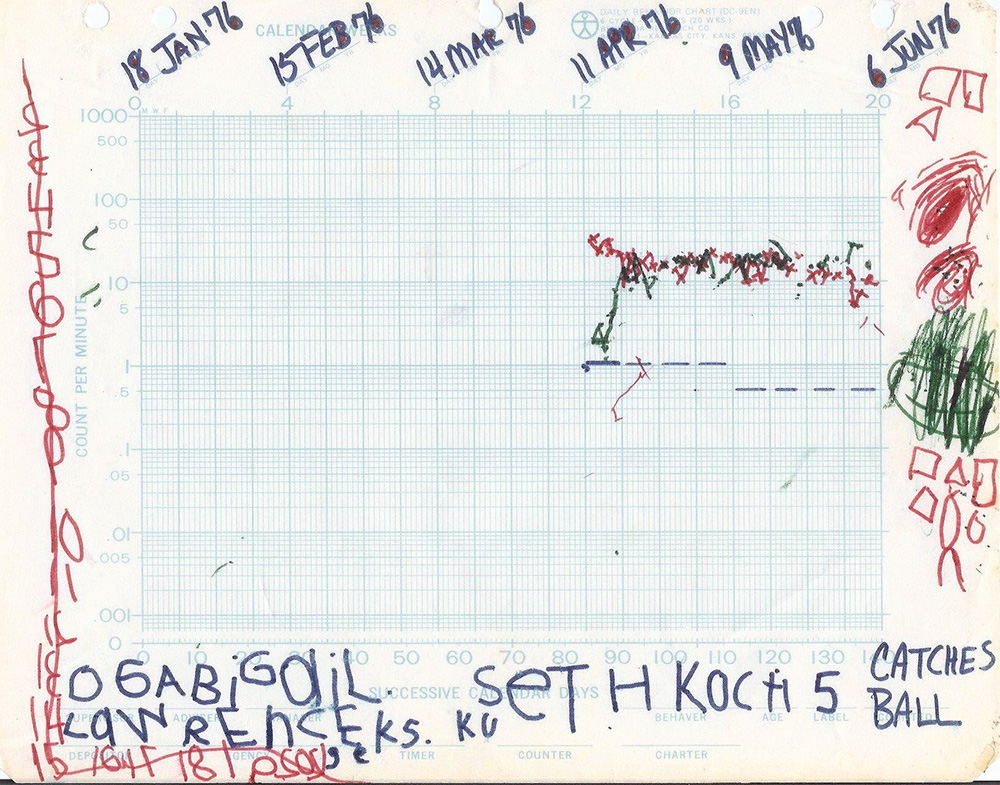

Here’s one of a little boy, my little boy, learning to catch a ball. The green are catches, the red misses the ball. To start, he put his hands up and turned his head away from the ball. I threw about 40 tennis balls per minute for him to catch. He had to look at the balls or have them continuously hit him. He looked. It the end of the project, he was catching more than he missed; the green is above the red. The project stopped because Seth went to Oregon for the summer.

|

Seth catches a tennis ball per minute. (Courtesy of Abigail Calkin) |

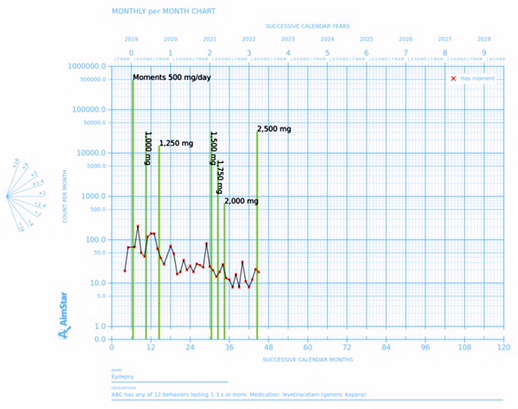

I’ll show you one more, a more recent one from a computer program, AimStar by Xcelerate Innovations. This is a personal one, epilepsy moments per month. Although I counted and charted them daily off and on since the 1970s, this is not a daily chart like Seth’s, but a chart of my monthly totals for the past three and a half years. I count twelve different behaviors, for example, hallucinates, has sensation of leaving my body, has vertigo, passes out, to give a few examples that comprise my epilepsy behaviors.

|

Abigail has seizure behaviors per month. (Courtesy of Abigail Calkin) |

My point in showing these charts is to show what kind of behaviors for tens of thousands of people can come out of one person’s wartime experiences. This doesn’t happen to every military person who serves in combat, but I know so very many other veterans have also offered much to the present and future of humanity. This is what Ogden Lindsley’s wartime experiences offered us: the ability to precisely monitor and improve human behavior.

I don’t show any academic behavior charts. You may google standard celeration charts to see lots of those. Google precision teaching to see more.

Additional histories about Ogden appear in The Soul of My Soldier (Calkin, 2015); Ogden R. Lindsley: His Life and Contributions (2023), Calkin (Ed.), and in many books, articles, and internet sites.

|